You Can't Bullet Point a Book

You're not in English class anymore. Why use apps or AI to cheat yourself out of getting the full experience of literature?

Did you know your local library sells books for very, very cheap? Even now, it still feels like a secret. Learning that I could buy books from the library—not just used ones, but brand new ones that were advanced copies or extra inventory—was one of the most wonderful discoveries of my young life. My family frequented three major libraries every week: the one in my town, the one in the town next to my town, and the one in the town we used to live in (close to where my dad worked).

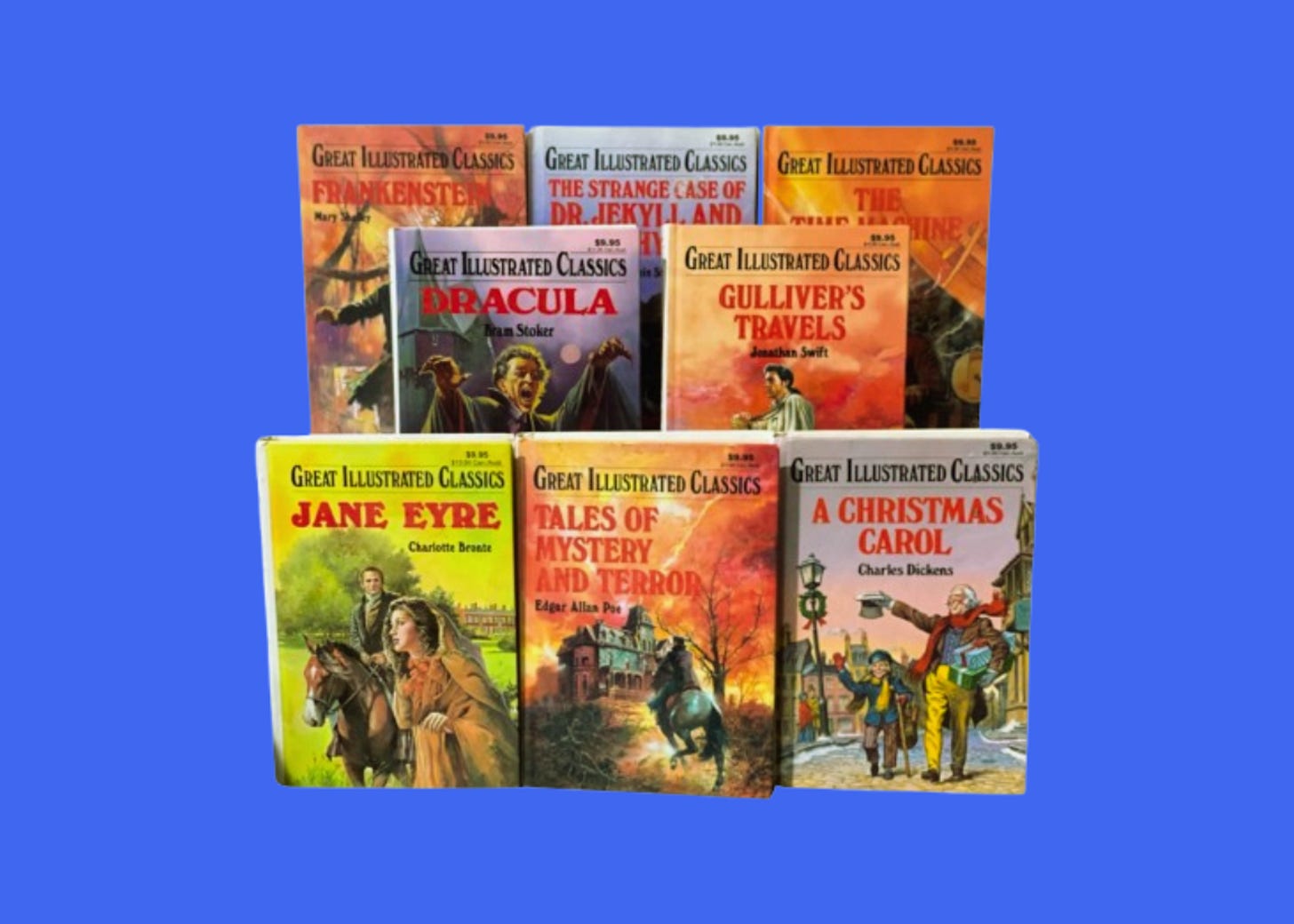

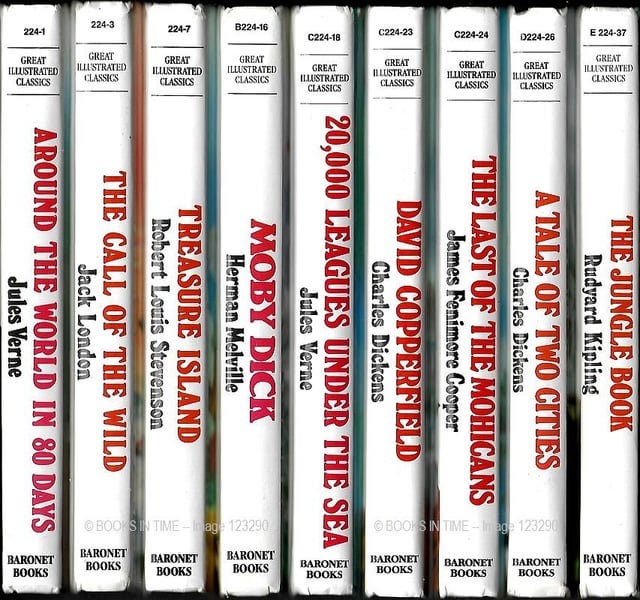

There were the books we checked out (usually 5 a week), and then there were the books we collected (this was done with more care and thought—buying only a few books every few weeks). My dad loved looking for the classics, and I still remember when he began bringing home The Great Illustrated Classics, each installation only a buck or two.

Classics has 66 titles in total. I read about 40 of them over the course of elementary and middle school, devouring The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Sherlock Holmes, A Little Princess, and Moby Dick. These books were my first foray into “real” literature. They were thick, substantial—proof, it seemed, of their authenticity. But their heft was largely thanks to bigger print and illustrations; each book was only 100 pages long, edited and revised for children to read. I felt accomplished until, years later, I learned the meaning of "abridged." I was pretty pissed when I realized I hadn’t actually read the "real" books.

In recent years, I’ve begun revisiting these titles—The Call of the Wild, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde were some of my favorites growing up and have only gotten better now that I’ve read their full, original texts. Other classics, like Frankenstein, I disliked as a child but cherish today. It’s hard to beat the genius and prose of Mary Shelley, but there’s really no way to get that to click for a ten-year-old. Hence, the beauty and wonder of Classics.

I definitely read less as an adult than I did as a child. I often have to force myself to read. But my philosophy today is simple: You’ve either read the book or you haven’t.

Reading is hard. It takes time, energy, and thinking, which makes it feel pretty incompatible with modern life. But this declaration is not merely pedantic; it is hyper-relevant in a world increasingly defined by the “bullet-pointification” of reading.

Maris Kreizman captured this phenomenon perfectly: "The popularity of book summary services... is a perfect encapsulation of what gets lost (nuance) in the bullet-pointification of books, in which every bit of information is served in digestible bite-sized portions that you can upload right to your brain." The rise of apps like Blinkist and AI-driven platforms promising to be the "Duolingo for knowledge" exemplifies this trend. These platforms claim to "fix" books by condensing them into summaries, "thunks," or interactive multimedia nuggets. As Kreizman pointed out in her newsletter this week, HarperCollins is already experimenting with AI-enhanced books that allow "conversations" with authors rather than just…reading the book.

WTF?

No one asked for this. Younger me was the victim of a bait and switch, not by choice, but by necessity! This isn’t true for adults. We don’t need technology to "improve" books; we need time, space, and resources for writers and editors to create meaningful work. And we all need to take time and space for ourselves, which is what reading helps so many people do.

Abridged versions exist for a reason: to introduce readers, often young or hesitant ones, to texts that might otherwise feel daunting. They’re an invitation into the text. But here’s the catch: an invitation is not the event. It’s a nudge to take action, to do the work of reading the full version. The problem arises when these simplified or shortened versions present themselves as replacements rather than introductions. Abridged classics should spark curiosity, not extinguish it.

This phenomenon extends beyond books. Every time I tap through my friends’ stories on Instagram, I see ads promoting apps promising to “replace scrolling with learning”—flashcard-like summaries of philosophical or literary texts, designed to be consumed in minutes. This sounds really nice. I do hate how much I scroll. But reading is separate from being on my phone—it must be, because close attention to the text and time spent in another world, on the page, is the point! The problem isn’t brevity itself; it’s the illusion that depth can be bypassed. Short versions of things—blurbs, abridged editions, even Instagram posts—should inspire readers to seek more, not settle for less.

The ultimate irony, of course, is that these tech-driven “solutions” are founded on a deep belief in the value of books. Why else would so many of these startups and apps market themselves as tools to make you a "better reader" or to "save" books? Even in their reductive form, books remain a cultural touchstone, a marker of intellectual aspiration. What these platforms often misunderstand, though, is that reading is not a means to an end. It’s a relationship—a lifelong conversation between the text, the reader, and the world.

Kreizman’s critique lands here, too: "We just need to give authors and editors and all of the people who work on books the time and space (and MONEY) to make something good. Sales of such books may not skyrocket, but they will become more valuable over time." To value books is to value the slow, deliberate process of reading them—and the communities and systems that sustain that process.

So how do we reclaim reading? Start where you are. Visit your local library (It’s literally free! And usually very nicely decorated, centrally located, full of comfortable seats, and beautifully quiet) and pick up a book, even an abridged one. Engage with it not as a substitute but as a stepping stone. Revisit a text you "sort of" know, and take the time to experience it fully. Reading is flexible; it’s forgiving. To be a reader is to embark on a lifelong pursuit—a relationship not just with literature, but with yourself. That’s what makes it rare and important. That’s why it matters.

Because at its core, reading is discovery. It’s an invitation to explore, to imagine, to connect. And no app, no AI, no summary can replicate the magic of holding a book in your hands and meeting it on its own terms.

It helps you meet yourself again, too.