Reading Translated Fiction Is Not About You

On Before the Coffee Gets Cold, the Bay Area Book Festival, and internet reviews.

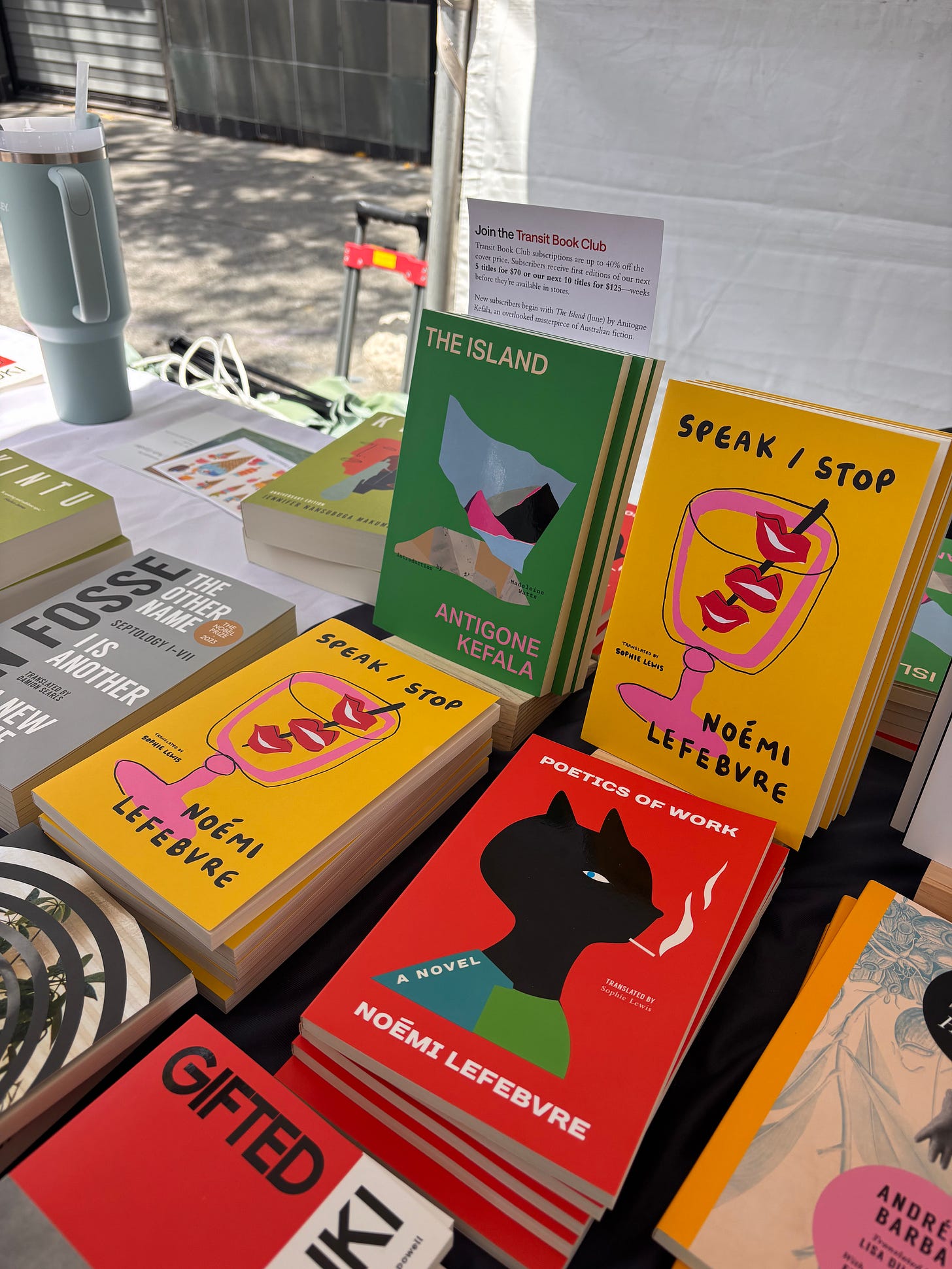

I spent more time than I care to admit at the Bay Area Book Festival this year debating whether to buy the $30 “Critic” hat from the Los Angeles Review of Books—and far less time than I truly wanted to at the beautiful stand run by Transit Books. It was the first time I’d encountered so many translated titles gathered in one place.

Transit Books, a San Francisco–based nonprofit publisher, has carved a distinctive place in the American literary scene, championing international voices with restraint, elegance, and an eye toward what endures. Their catalog includes names both obscure and newly beloved: Antigone Kefala, Suzumu Suzuki, Noémi Lefebvre—and Jacqueline Harpman, whose I Who Have Never Known Men has become something of a cult object on Instagram and Goodreads alike.

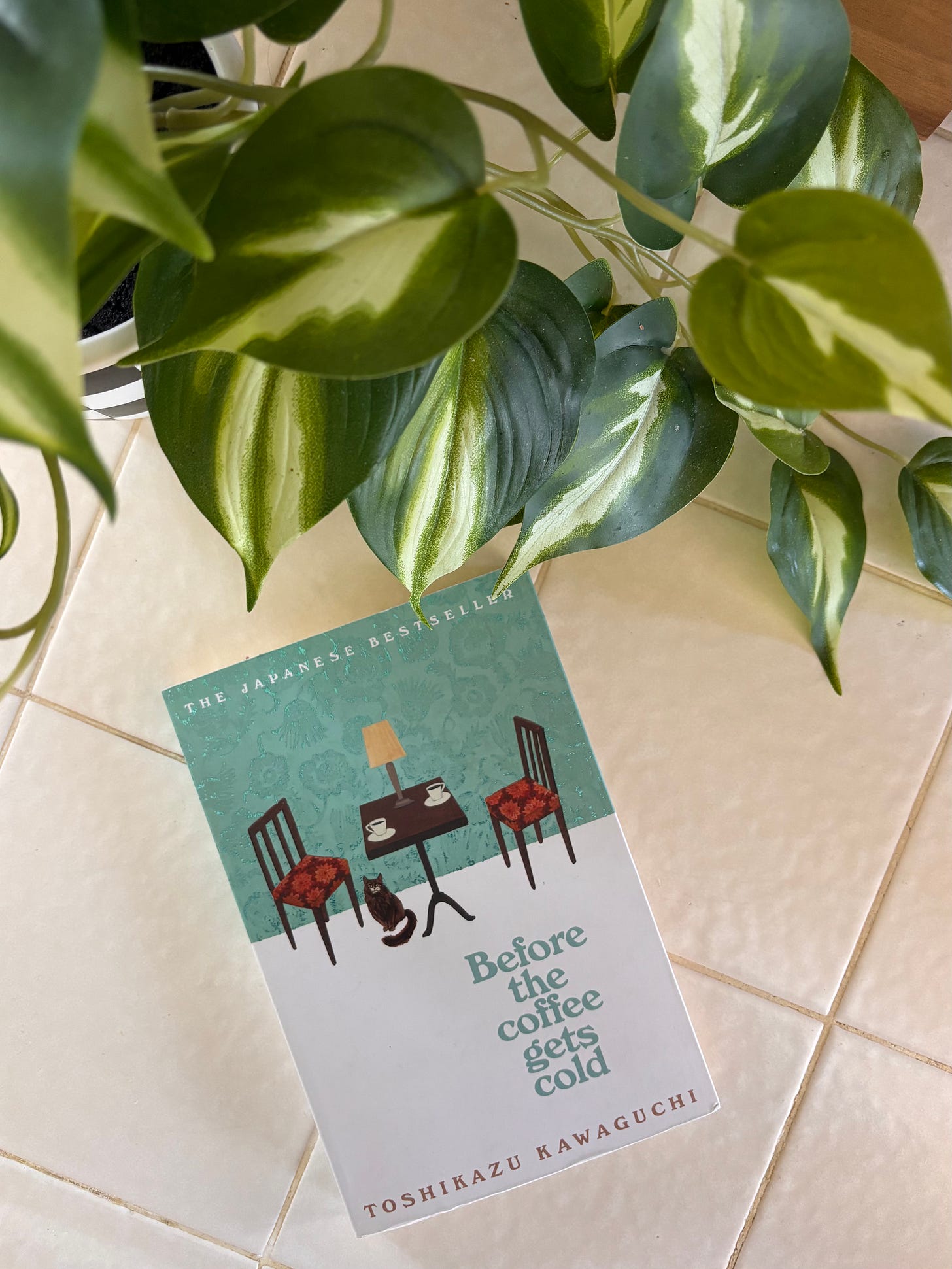

For most of my reading life, translated fiction remained peripheral—an idea I brushed against only online, or in foreign bookstores abroad. But the week of my graduation, I picked up a copy of Before the Coffee Gets Cold, a slim novel by the Japanese playwright Toshikazu Kawaguchi. The US edition, translated by Geoffrey Trousselot and published by Hanover Square Press (imprint of HarperCollins), has gained some popularity in recent time. I found the book lying on the English department’s designated “Free Books” bench, as I walked through the building for the last time.

The title struck me with its urgency and instruction. I walked at graduation, packed up my college apartment, and began reading the next day, in the first place I would live after.

In a small Tokyo café, customers are allowed to travel back in time—though only under a rigid set of rules. You must sit in a particular seat. You may only speak with someone who has also visited the café. And most crucially: you must return before your coffee gets cold.

Kawaguchi’s novel unfolds in four vignettes, each a subtle variation on the same moral conceit: a character returns to a past moment, and though the facts of the timeline remain fixed, something imperceptible shifts within. Kawaguchi’s prose is spare to the point of translucence—sometimes distractingly so. Dialogue is delivered plainly, and exposition often substitutes for interiority. But this stylistic restraint feels less like oversight than intention. There is a studied flatness to the narration, reminiscent of fable or stage direction, that allows the emotional weight to accrue not through flourish, but through repetition and ritual.

Kawaguchi is not interested in surprise; he is interested in structure, in return, in the quiet rhythms of regret. His sentimentality is neither ironic nor disguised—it is sincere, even ceremonial, and in this way the novel operates more as a modern parable than a conventional psychological narrative. The result is not subtle realism but affective allegory: a story not about how time changes us, but how we learn to sit, however briefly, with what cannot be changed.

Much of the legible criticism surrounding Before the Coffee Gets Cold (which any quick Google search will reveal) echoes a familiar refrain often lobbed at translated fiction: the prose is too plain, the characters too unrelatable, the values too dated, the pacing too slow. These judgments surface again and again, particularly from readers accustomed to the interior complexity and cathartic arcs of contemporary American literary fiction. But as Kawaguchi points out in the book, “People don’t see things and hear things as objectively as they might think.” Beneath the surface of such critiques lies something more telling than stylistic preference—they reveal an unease with coming up against narrative forms that don’t conform to our own literary sensibilities. A different emotional tempo. A different narrative architecture. A different idea of what fiction is for.

We forget, I think, that all reading is cultural translation. What we often call "good writing" is simply writing that fits the tonal and structural norms we’ve been trained to value: irony, psychological realism, narrative tension, interior monologue. When those conventions are absent, the instinct is often to dismiss the book itself, rather than question the critical vocabulary we’re applying.

When I reflect on how I evaluate books, I rarely ask whether I liked them in the immediate, consumer-satisfaction sense. Instead, I ask: Did the book accomplish what it set out to do? Did it fulfill the logic of its own world? Did it remain faithful to its own mode of telling? When I say this aloud, people often look at me as though I really am wearing the $30 “Critic” baseball cap I considered buying in Berkeley. But I stand by this framework because it offers the most lasting satisfaction as a reader. It opens space for encounter rather than judgment, for curiosity over comparison.

And nowhere is that approach more essential than in reading translated literature. These are books that already contain an act of transformation—language into language, culture into culture—and to demand they behave like American novels is to flatten the very exchange they make possible. Translated fiction often resists our familiar narrative pattern, not from deficiency, but from difference. It asks us to adjust our rhythm. To listen more closely. To admit, perhaps, that our taste is not the measure of all things.

Kawaguchi’s novel, I think, does exactly what it intends. It offers not reinvention, but ritual; not transformation, but repetition. No dramatic turns, no ironic reversals. Just a quiet belief that words left unsaid deserve a second hearing—not to alter history, but to make peace with it.

This is not to suggest that Before the Coffee Gets Cold is a perfect novel. It isn’t. Novels rarely are, which is exactly why we read them and keep reading other novels. But it operates within a coherent emotional architecture—subtle, meditative, consistent. And if we find ourselves frustrated by its simplicity or its sentimentality, perhaps the more compelling question is: why?

Too often, American readers evaluate translated fiction against domestic expectations. We crave momentum, interiority, voice. When a work resists those demands, it’s labeled flat. Or worse: boring. But these judgments often reflect our own habits more than the book’s shortcomings. They reveal a discomfort with unfamiliar rhythms. A preference for conflict over contemplation. A hunger for novelty, even in our grief.

To read translated fiction well requires more than comprehension—it requires suspension. A willingness to be disoriented. To listen, rather than project. If we approach every novel with the same rubric every time—Was I entertained? Did I relate? Did the ending surprise me?—we risk missing the deeper promise that translation offers: a chance to inhabit a worldview that doesn’t bend to ours.

Before the Coffee Gets Cold doesn’t ask to amaze you. It, like all books, asks you to sit down, stay a while, and listen before the moment passes. And if that leaves you restless, perhaps the problem isn’t with the book—but with what you’ve grown too used to expecting.