Precious Fruits

A response to Lyz Lenz on cruel children and hungry mothers

“There is so much love in food and so much grace in its giving. In Take This Bread, by Sara Miles, she quotes a bishop who told her, ‘There is a hunger beyond food that is expressed in food, and that’s why feeding is always a miracle.’ This is why meals are so fraught in our home. Because food is never just food. It’s my labor, my offering. But how can a child know that? How can they understand that homemade cinnamon rolls every Sunday are supposed to say something that I cannot form with my words? All they know is the taste and their own immediate need.” - Lyz Lenz, Endless Preparation and Women’s Work

At six-years-old, I began my first-ever--and only--hunger strike. I screamed, cried, and begged my parents for days to oblige my cause. Yet they could not. My mom continued as she always had, ladling out steaming servings of rice porridge with fermented bean; piles of my favorite stir-fried eggplant and pork dish; and heaps of mapo tofu onto my plate and into Tupperware lunchboxes.

I refused to eat.

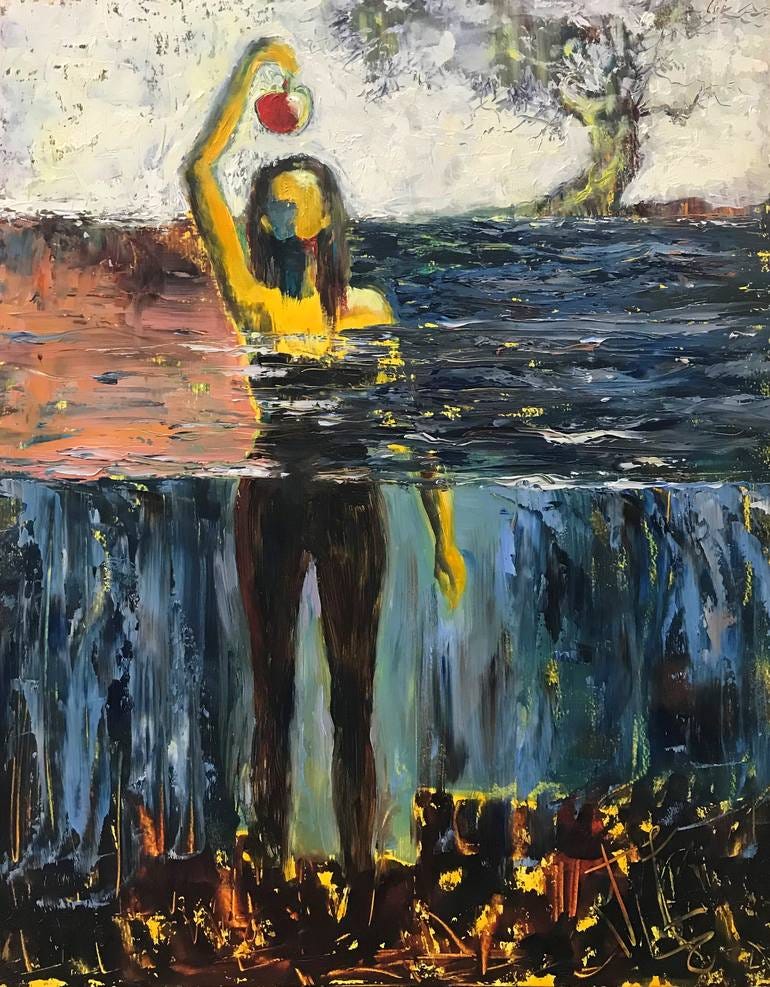

She cored juicy, crimson apples; sliced sweet golden pears; and toiled over unrelenting pomegranates. She spent entire nights emptying those fruits of their precious seeds.

I refused to eat.

I refused to eat because I could not bear to bring my mother’s home-cooked food to school. While addition still escaped me from time to time in kindergarten, even at age six, I knew how to count what really mattered: one point if you had sleepovers every weekend, one point if your mom signed up to read English books to the class on Fridays, one point if you went to Disney over the summer, and one point for every snack you could share at lunch.

While I struggled with winning any of the above points, it was the last one that I grieved the most, because it felt so basic. How could the very way I nourished my small body betray me so deeply?

As I solemnly ate my homemade dumplings, my classmates feasted on peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, Lunchables, and Goldfish crackers. They peeled off sticky Saran wrap from their cold pizzas, licked the tops clean from their berry yogurt containers, and traded melting red and blue Gushers.

Nothing had ever looked more filling.

Eventually, split between watching their child waste their hard-earned food or letting her simply buy lunch at school, my parents chose the latter. For the rest of my K-12 career, they dutifully put $500 on my school account each year so I could eat whatever prepackaged foods I wanted at school. Even when my school lunches were sopping piles of green beans and plasticky mac and cheese, I refused to trade in for my mom’s own delicious, Chinese cooking; I was okay with suffering through the nutritional pitfalls of the public school system if it meant that I, for once, had what everyone else seemed to have. I would spend the rest of my life clawing desperately for that brief, beautiful taste of sameness. I am the same as you. We have the same mother. We grew up in the same house. We eat the same snacks. We are equals.

After reading Lyz Lenz’s essay, “Endless Preparation: Apples and Women’s Work,” I now wonder if my mother, on the opposite end of my childhood sorrow, had been seeking this “sameness” as well. When Lenz’s children refused her breakfast that morning and instead reached into the trashcan hours later to fish out the sticky, gross remains of it to eat, did my mother see herself and her heritage-hating, white-washed daughter who would rather fill her body with all-American artificials than the meals she spent hours cooking every day?

My mother, like Lenz in her essay, “I'm a Great Cook. Now That I'm Divorced, I'm Never Making Dinner for a Man Again,” learned how to cook to fill the void; while in China, she had been a successful lawyer, in America, it meant nothing. She meant nothing. She could not work, she could not go to school, and she could not even give her child the white suburbia bliss she craved so desperately. There was no Disney, there were no parent-class storytimes, and there were no sleepovers. Such things did not exist in my parents’ childhoods, so they struggled to see how they fit into mine.

Lenz gave voice to what I imagine immigrant mothers wonder all the time: “Weren’t my offerings good enough for you? My children are cruel little deities who reject my best offerings for trash [...] I think of the trees creating their fruit and dropping it to the ground. The offerings gone to waste, the labors ignored. Is this my life, to labor always, whether or not my offerings are deemed worthy?”

While it does not escape me that Lenz is a white woman, her writing surprisingly embodies a popular metaphor in Asian-American culture of “cut fruit”: so many parents who struggle to utter “sorry,” “forgive me,” “I love you,” yet show their care through plates of peeled and sliced apples, pears, and pomegranates. It took me a long time to understand this offering--as long as it took me to forgive myself for simply not being born white, or male, or wealthy.

As a child, I did not reject my mom’s cooking because it was not enough for me; I rejected it because it was not enough for my survival. I did not “refuse to be full”--I was not full. I feared I would never be full, or whole, or enough in the world I was raised in--and Lenz’s writings have made me realize mothers, especially displaced ones, feel the same. We are all shackled to the same fate as Tantalus, forever under that plentiful, cruel fruit tree.

Funnily enough, Lenz’s writings have made my own heart and hands feel restless; I too wish for my mother to exist in a glorious, unencumbered existence, not because she expects it, but because she should.

I will plate the sweet fruits of this new country for her: forgiveness, understanding, and rest.

This is so heartfelt and genuine. It made me reflect on my own elementary school lunches, where I begged my parents to buy me a specific yoplait yogurt because I thought it would make me fit in. It's crazy how I thought a dumb $1 yogurt would do so much and try to make me feel equal and white like you said so well in your paper.