Goodreads: The Platform for Radicalization or Just Another Reading List?

Maybe we are reading too much into what someone reads. Or not.

Goodreads, like many projects, began at a kitchen table. I wonder if Luigi Mangione ever found himself there, trying to come up with a simple solution for a complex problem. (Important to emphasize trying).

Founded by Otis and Elizabeth Khuri Chandler in 2006, the platform has always felt innocent—naive, even, amongst its social media peers. I think this is largely because of how straightforward and invariant it is: the point of Goodreads is to help people catalog and share their reading lists. Its purpose and utility hasn’t changed in nearly two decades. And because of that, it remains one of my favorite social media platforms. I’m always eager to introduce friends to it, and I log back in every few days to see if they’ve started or finished a new book or perhaps written a review of something I love, dislike, or have yet to read. Ideally, I contribute an update of my own, too.

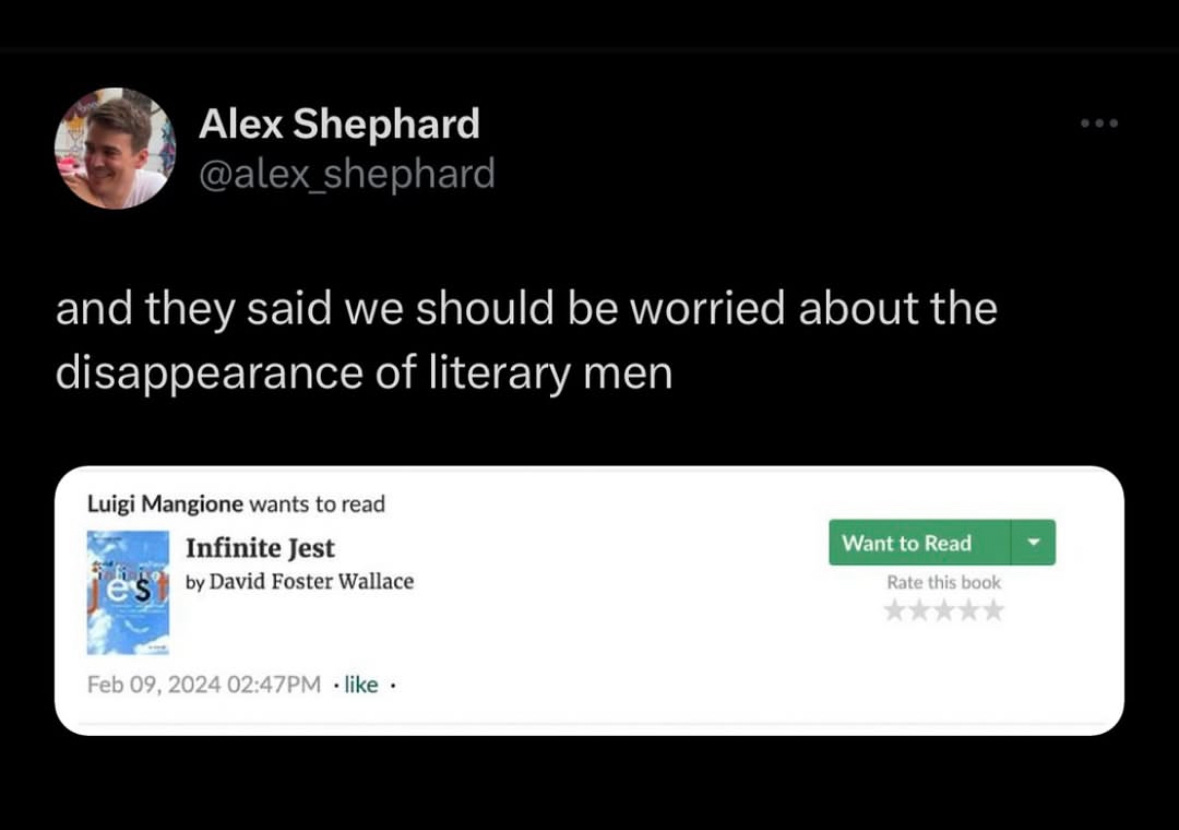

Who knew that this modest platform would someday captivate the public’s attention in a mainstream murder case? In the wake of the UnitedHealthcare CEO shooting, Luigi Mangione’s Goodreads account has become a source of fascination, less a simple reading list and more an ideological artifact. The account is now private, but not before the internet could get a hold of it. Screenshots are still in circulation on platforms like Reddit. Weirdly, this scrutiny has sparked renewed interest in literature and its relationship to a young person. We are now all reminded of its enduring role in shaping—and revealing—human thought.

But what can a Goodreads account really tell us about a person? Mangione’s reading history offers some interesting juxtapositions. You have The Lorax and then you have Industrial Society and Its Future—also known as “the Unabomber manifesto.” If there is a unifying thread, it might be a critique of industrial modernity. Or, alternatively, the algorithm’s tendency to write suggestions like “Readers of George Orwell might also like… Ted Kaczynski.”

Reddit commentators on the gossip subreddit, r/fauxmoi, observe that Mangione’s literary tastes grew darker after 2020, coinciding with a politically tumultuous period in America. This makes sense, given the chaos of the first Trump election, large-scale social justice movements, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet his book choices do not so much construct a portrait of radicalization as they reveal a common archetype: what cultural historian Mark Harris described on Bluesky as “a very recognizable type of young male ideology tourist.” Consider the pattern: Sapiens for evolutionary perspectives, Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind for explorations into consciousness, and Ray Kurzweil’s The Singularity is Near for techno-utopian musings. Add Moby-Dick to the “Want to Read” shelf for literary ambition—a rite of passage for many—and the profile emerges of a Silicon Valley libertarian archetype, intellectually curious yet ideologically unmoored.

Mangione’s review of the Unabomber manifesto has particularly captured the internet’s imagination. He describes it as “clearly written by a mathematics prodigy” and “reads like a series of lemmas on the question of 21st-century quality of life.” His academic framing—“a series of lemmas”—renders his analysis oddly detached, almost clinical. There’s no question that Kaczynski was indeed a mathematics genius; he and Mangione are certainly considered peers if we loom at academic affiliations alone. At the same time, he acknowledges Kaczynski’s violent actions, but from the position of a “political revolutionary.” rather than a criminal. The review walks a fine line, one that raises questions: Did Goodreads’ recommendation engine amplify latent radical tendencies, or was it merely a mirror reflecting Mangione’s evolving worldview? How do we encounter texts like this in the first place? How are those encounters shaped and influenced? And how do we separate readers from what they read?

This leads to a broader cultural debate about access to politically controversial texts. In an era when libraries are under siege and calls for book bans abound, should texts like the Unabomber Manifesto or Mein Kampf remain freely available?

At first glance, it may feel that having such works in circulation still can incite harm, yet Mangione’s reading list suggests a more complex picture. Alongside these contentious titles are bestsellers like Freakonomics, The Four-Hour Workweek, and a biography of Elon Musk—books emblematic of a mainstream, self-improvement ethos. His literary habits appear less subversive than reflective of a privileged, well-educated background steeped in tech culture and individualism. In all honesty, his Goodreads just looks exactly what I would expect from a UPenn graduate, Stanford high school program counselor, and tech company engineer. I know many of them personally. I go to school with them now. (Plus, not to mention that the texts that so-called advocates are actively working on censoring these days are works like picture books about LGBTQ+ identity, chapter books that mention sexual pleasure, and classics that advocate for racial equality and a reckoning with white supremacy. Regardless of this conversation, we should all be very concerned about those books continuing to be removed from public schools and libraries.)

But perhaps the most troubling aspect of Mangione’s story is not what he read, but when he stopped reading. By 2023, his activity on Goodreads had dwindled significantly. As A.O. Scott notes in The New York Times (in an article that I will also mention was categorized as a “Book Review”), reading often serves as a moderating force, a way to engage with challenging ideas without acting on them. Immersion in a book provides a safe space for exploration, a buffer between thought and deed. When the books close, however, and the boundaries between isolation and ideology blur, what remains?

Mangione’s story resists simple conclusions. Was his reading a catalyst for violence or merely a symptom of broader discontent? Did it radicalize him, or was it a passive reflection of his intellectual wanderings? Or did he just forget to log the reads that followed, and eventually decided, as even the most enamored Goodreads user does every so often, to just log in again later? There are many, many questions left in this case. But for the moment, it feels like one thing has emerged as fact already: Goodreads has evolved beyond its role as a literary platform. Maybe not during this week exclusively. Maybe it evolved from the moment it was brought into this world. Either way, I think it has always served as a cultural archive, a repository of the ways we seek, process, and share ideas. In many ways, it even has a similar position to Substack. But now, it’s no longer just reviews between friends. Or at least, that’s not how many of its longtime users, including me, see it. What we read, write, and think online lives in the real world.

And in this case, these ideas underscore the lasting power of literature—not just to provoke thought, but to incite debate about its very role in society.

"This leads to a broader cultural debate about access to politically controversial texts. In an era when libraries are under siege and calls for book bans abound, should texts like the Unabomber Manifesto or Mein Kampf remain freely available?"

Coming from a librarian, the stance of the profession as a whole would be to provide access to any and all information regardless of content, which is called the Freedom to Read. I personally don't believe people should be reading bigoted rantings by conservative pundits, but it's also not my business what others choose to read. And anyway, I think that vulnerable people are indoctrinated in hateful ideology in social circles, mostly online these days, rather than by which books they choose to read.

Everything is a Rorschach to one who sees.