Girl Math, Girl Dinner, Girl Music: The Dumbification of Female Language Use Online

What the rise of Sabrina Carpenter’s linguistic “nonsense” and other Internet terms tells us about the state of feminism today

On August 10th, 2024, Sabrina Carpenter stepped into the spotlight at Outside Lands, headlining her first major music festival after a last-minute cancellation by Tyler the Creator. In knee-high platform boots and a sparkling black dress, she electrified fifty thousand fans, including myself, in Golden Gate Park, leading a chant that echoed far beyond the cypresses: “That’s that me espresso!”

But what does that phrase actually mean? Is “That’s that me espresso” an appositive, an autocorrected error, or simply a syntactic anomaly? The truth is, in today’s landscape of digital communication, it hardly seems to matter. In an era where phrases like “girl math” and “girl dinner” dominate online discourse, nonsensical language has become a form of expression that thrives on its very lack of clarity. This kind of linguistic playfulness reflects a broader cultural shift, where the meaning of words is often secondary to their shareability and immediate impact.

The line “That’s that me espresso” exemplifies how language today often functions more as a quick jolt of absurdity—brief, intense, and designed to stimulate just enough to keep the conversation going, without inviting deeper reflection. It’s the linguistic equivalent of a shot of espresso: sharp and effective, but not exactly nourishing. Yet, beneath this seemingly playful nonsense lies something more intriguing.

The popularity of phrases like “girl boss,” “girl math,” and “girl dinner” over the past year points to a deeper cultural shift. These terms, endlessly hashtagged, memed, and repurposed, seem harmless at first glance, but they raise questions about what they’re doing to our language—and to us. Language has always been a tool of power, and how women wield it, even playfully, reveals much about the societal forces shaping our lives. The rise of these “girl” terms seems to be signaling a tension between reclamation and regression. They are ironic badges of a digital girlhood, a way to wink (perhaps while in a mini dress, boots, and perfectly blown-out curtain bangs) at patriarchal norms while navigating the suffocating expectations of late capitalism. But is this wink at convention truly empowering, or does it blur the line between liberation and self-sabotage?

When Irony Digs Its Own Girl Trap

The linguist Penny Eckert has written extensively about how language both reflects and shapes social identity. Adding “girl” as a prefix to terms like “boss,” “math,” and “dinner” isn’t just a way to feminize traditionally male spaces—it’s a way to mark those spaces as unserious, ironic, and self-contained. Eckert calls this process “indexicality,” where language choices signal our position in the social world.

In these “girl” terms, there’s a sly in-group humor at play, that performative shrug that says, “We know this isn’t how it’s supposed to be, but isn’t it fun to pretend?” It’s an irony that leans into Eckert’s concept of “covert prestige,” where language is used to signal belonging to a subculture—in this case, young women who are keenly aware of how they’re expected to perform femininity under capitalism.

But irony, as we know, is a slippery thing. It can cut both ways, often leaving behind the very stereotypes it claims to mock. “Girl math” began as a joke about rationalizing frivolous purchases—justifying that $300 coat by breaking down the cost per wear (“If I wear it everyday for the next year, then it’s actually less than a dollar!”) until it feels like a steal. But the joke quickly morphed into something darker, normalizing financially reckless behavior while dressing it up as empowerment. Suddenly, what was meant to poke fun at consumerism becomes a way of reinforcing it—another way we slip deeper into capitalism’s grip while laughing at how clever we are.

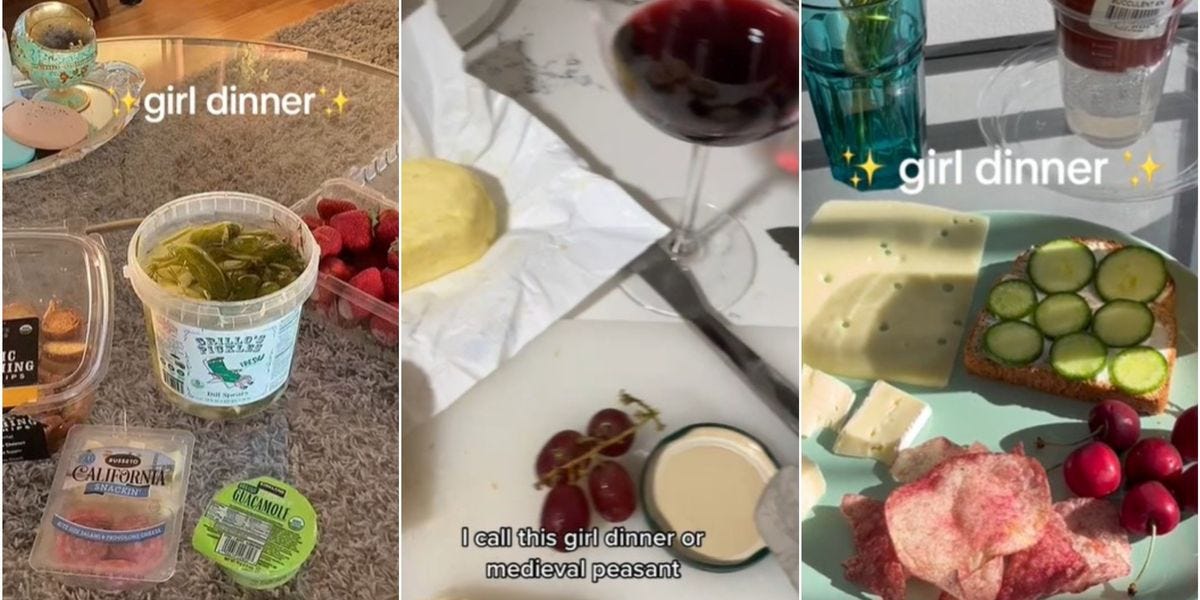

Then there’s “girl dinner,” the aestheticized version of disordered eating that’s been repackaged as quirky and minimalist. A plate of cheese, olives, crackers, maybe a few grapes—photogenic, effortless, and, if repeated enough times, a recipe for nutritional deficiency. What looks like a fun little meme about not having the energy to cook is, when you dig deeper, a reflection of the exhaustion that defines so much of modern womanhood. We’re meant to see these meals as “chic” or “cute,” but there’s something deeply unsettling about how closely they mirror restrictive eating patterns that, if sustained, slide from self-care into self-harm.

What makes these “girl” trends so sticky is how effortlessly they blend humor and harm. They package genuine anxieties in a form that’s easy to laugh at, easy to share. And that humor—what linguist Deborah Tannen might categorize as ritualized self-deprectation—is where the danger lies. Tannen’s study of the communication differences between men and women shows how women often downplay their knowledge or authority through irony and humor, making these “girl” terms a kind of linguistic armor: deflective, playful, and, ultimately, self-defeating.

The Comfort of “Brain Off” Content

We’re living in a world where cognitive overload is the norm, and “brain off” music like Carpenter’s serves as a kind of linguistic fast food—quick, tasty, and devoid of real substance.

The success of Carpenter’s nonsense lyrics isn’t just a quirk of pop culture; it’s a response to a world that’s become unbearably overstimulating. The endless notifications, the pressure to optimize every aspect of our lives—there’s something cathartic about letting it all go, about zoning out to a song that makes no demands on our intellect. But what does it say about us that we crave content designed to turn our brains off?

Maggie Nelson, in The Argonauts, explores the tension between fluidity and fixity in identity, suggesting that in a world obsessed with categorization, opting out can be a radical act. Carpenter’s music, stripped of meaning and saturated in catchiness, offers that opt-out. “That’s that me espresso” isn’t meant to be understood; it’s meant to be enjoyed. And in a landscape dominated by the attention economy, that’s exactly the point. The phrase works because it’s nonsensical, because it invites you to stop making sense and just let the beat carry you away.

But why are we so drawn to this kind of content? Social media platforms reward engagement with content that offers immediate, low-effort rewards. We’re living in a world where cognitive overload is the norm, and “brain off” music like Carpenter’s serves as a kind of linguistic fast food—quick, tasty, and devoid of real substance. In this environment, language becomes a commodity, stripped of depth in favor of shareability. What sticks is what’s easiest to consume, not what’s most meaningful.

The Contradiction of Triviality

It’s easy to dismiss these trends as harmless fun, but they reveal a deeper contradiction in how women navigate identity in the digital age. Judith Butler’s theory of performativity suggests that gender isn’t something we are; it’s something we do, over and over, until it feels natural. The repetitive use of “girl” in phrases like “girl boss” and “girl math” is an example of this performativity—it’s a way of doing femininity that’s intentionally unserious. But as theorist Lauren Berlant argues, this kind of performative triviality often leads to what she calls “cruel optimism,” where the things we latch onto for hope end up being the very things that keep us stuck.

Sara Ahmed’s work on “feminist killjoys” is also relevant here. Ahmed argues that resisting the cheerful, superficial norms of performative positivity often gets you labeled as a buzzkill. By embracing the absurdity of “girl” language, young women sidestep the exhausting demands of seriousness. It’s a way of participating in culture while keeping one foot out the door, a linguistic sleight of hand that lets us have our cake and eat it too—until we realize that the cake was mostly air (girl dinner!)

The Trap of Commodification

The viral nature of these trends can’t be separated from the commercial forces driving them. Online spaces like TikTok operate on a logic of virality, where the most successful content is that which can be easily packaged, shared, and, ultimately, sold back to us. The commercial potential of “girl” language is enormous—what starts as a subversive in-joke quickly becomes another tool for selling products, lifestyles, and, of course, more content. This is the central tension: what begins as a playful rebellion is quickly co-opted by the very systems it seeks to critique.

The commodification of “girl” language highlights the limits of linguistic resistance within a capitalist framework. We think we’re in on the joke, but the joke is ultimately on us when these terms are repurposed to market everything from skincare to coffee mugs. The concept of the linguistic marketplace is useful here: language isn’t just about communication anymore; it’s a product in itself, subject to the same cycles of commodification as anything else we consume.

The Price of Playing Dumb

The rise of “girl” terms and the embrace of “brain off” content like Sabrina Carpenter’s music reflect a collective exhaustion, a desire to disconnect from the pressures of always having to be correct, coherent, and critical.

The supposed “dumbification” of female language online is neither wholly empowering nor entirely disempowering—it’s both at once. It lives in that murky space between irony and sincerity, between resistance and complicity. As Eckert and other sociolinguists remind us, language is always in flux, shaped by and shaping the social worlds we inhabit. The rise of “girl” terms and the embrace of “brain off” content like Sabrina Carpenter’s music reflect a collective exhaustion, a desire to disconnect from the pressures of always having to be correct, coherent, and critical.

Yet these linguistic performances are fraught with contradictions. They offer a temporary escape, but only within a system that quickly absorbs and commodifies them. This self-defeating use of female language is, in many ways, a survival strategy—one that makes perfect sense in a world where the only way to make sense of things is to stop trying. But it’s also a symptom of a deeper cultural malaise, a recognition that sometimes the only way to keep going is to revel in the absurdity, even if we’re just spinning our wheels in the process.

Ellen Yang studies English and Linguistics at Stanford University. She is deeply interested in language and how it impacts and informs our digital behaviors, with a strong research interest in discourse analysis and typology. She is currently working on a literary fiction novel. Outside of writing, she leads marketing at tech startups. Please consider subscribing so she can escape.

The effects of social media and subsequent linguistic habits are so interesting. It’s definitely an underdiscussed topic in both feminist spheres and mainstream social media. I absolutely loved reading this article and can’t wait to read more pieces from you 🤍

I have often had similar thoughts on the commodication and overuse of "girl" terms and phrases like "That's that me espresso." Ellen Yang clearly addressed the issue in a navigatable manner looking deeply at the roots and harvest of these trends. This is a wonderful article and I can't wait to see mote from Yang. :)