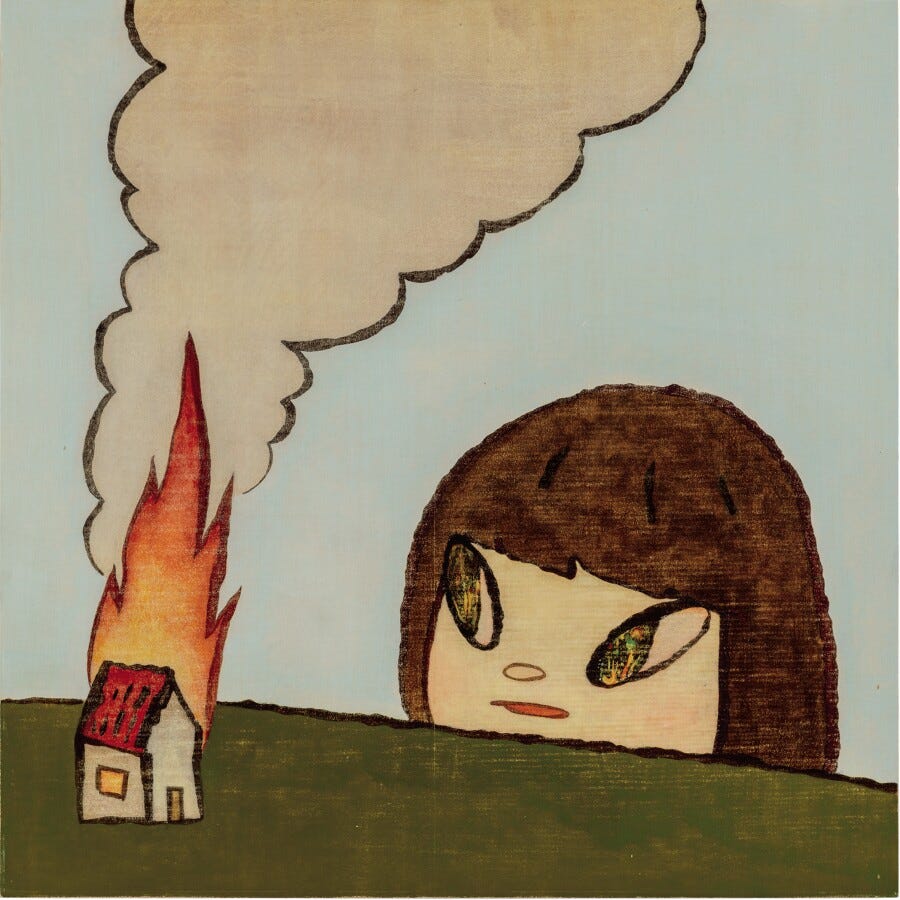

Burn This House

Yes, they’re back. After a decade of trying every version of the modern office imaginable, why is Silicon Valley suddenly obsessed with startup houses again...and why is it so dangerous for feminism?

Apple was built in a garage.

Facebook was built in a dorm.

Virgin was built in a high school bedroom.

That was the era between 1997 and 2006, back when a few kids hooked up to the internet in their dorm room or garage and a venture capitalist willing to take a shot on their idea was enough to scale the dot-com boom to millions. By the time the smartphone boom hit in 2007-2016, however, early hires wanted to retire the dirty, scrappy garage story in favor of shiny, kombucha-on-tap offices in major cities; after all, affording an office post-Great Recession was a coveted privilege and a strong indicator that a startup was serious.

At the end of 2019, San Francisco, the heart of Silicon Valley, had an office vacancy rate of only 3.7%. By mid-2022, however, that rate was at 24.2%, reflective of a mass pandemic exodus.

Where did these companies go? Well, for some, they died. Others, they went home. But for some new players, they traded in WFH and office culture for something else: a house the whole team shares together.

Yes, they’re back. After a decade of trying every version of the modern office imaginable (see: WeWork), why is Silicon Valley suddenly obsessed with hacker/startup houses again?

In its prime, Launch House was both an incubator for startup founders and a social club with hundreds of young members across the tech spectrum. For a yearly fee of $1000, founders and startup aficiandos could join as a general member, with access to its Discord channel, its Beverly Hills mansion and New York City space, and fun networking events. For a one month fee of $3000 and an exciting application, however, founders could join a cohort of two dozen other members, living and working together for a month. The cohorts quickly rose to popularity within tech circles and attracted the attention and mentorship of prominent VCs and advisors. In March 2021, Launch House launched its inaugural all-female cohort with the goal of cementing its community as the ultimate pioneers of the second wave of startup houses, leading Silicon Valley to its next Golden Age. By the cohort’s conclusion, however, the only thing impressive about Launch House was its horrifying ability to put so many women repeatedly at risk within its space, leading to multiple incidents of sexual assault and harassment within only a few weeks. For example:

During a heavily alcohol-fueled outing on a party bus in April 2021, several cohort members harassed the women on the bus, before one of them allegedly stuck a hand up the skirt of a member I’ll call Jessica (not her real name). After the incident, according to sources, Goldstein and Peters asked Jessica to rate, on a scale of 1 to 10, how much each of the men violated her. Launch House denies that Jessica was asked to do this. In a few days, only the man whom Jessica had ranked the highest was kicked out of the house. None of the women were given a heads up that he was being told to leave, and were therefore stuck in the house with him as he packed his belongings, Jessica said.

While Jessica remained disturbed by this experience, she felt that the opportunities presented to her by the community were still too good to pass up. She rejoined Launch House for another cohort after the bus incident, during which, she says, things only got worse.

When Vox published its damning exposé in September 2022, Silicon Valley was shocked—or at least the men were. But for women in startup, it was an old, painfully familiar tune: the informal policies/structures that are disguised as “chill” rather than the unsafe and unprioritized realities they truly were; the insurmountable amount we are willing to give of ourselves for a chance at our dreams, and the equally Herculean amount of predatory behavior we are consistently met with in this space; and, of course, the victim of sexual assault who returns back to the institution that hurt her, because it is “worth it.” It has to be, right?

When Jessica woke up the next morning, she, along with several other women who’d attended the party, was pretty sure she’d been roofied. She only remembered taking three shots — not nearly enough to black out for her tall frame — but woke up in bed without her tampon in, and without knowing how or when it had been removed or how she’d gotten upstairs. Other people at the party, too, reported instances of blacking out due to suspected drugging, noting how weak the security had been, how none of the bedrooms had been locked, how essentially anyone could walk through the door at any time. And they did: Multiple people reported seeing groups of partygoers enter the bedroom where Jessica was passed out. Onlookers presumed they were en route to the attached bathroom to do cocaine.

Jessica eventually went to the hospital for a sexual assault forensic exam and decided to spend the next few days at a hotel to process what had happened. In the meantime, the police came to the house again, as part of an investigation into an alleged assault with a deadly weapon, according to records. A member who was at the house that evening saw the police flipping through CCTV footage from the property. “Everything was tense,” said one member. “We couldn’t get any straight answers from the founders. We were told that police were coming and to just keep going about our day, and not talk to them if they asked us anything.”

Launch House is the tragic zenith of a recent trend in startup: the return to co-living and startups as a household. Launch House itself is actually a meta concept of a pretty simple idea: startups exist solely to scale as fast as they can. And certainly no startup grows faster than the one that takes over everything: your home, your meals, your free time, your social life, and all the things that usually exist outside the traditional office.

Sure, these houses once were—and perhaps may be again—ground zero for unicorns, but what is the cost on its workforce, especially as more and more women enter tech? What can we learn from understanding unconscious gender dynamics and the sudden ideological return back to the 2000s-style “startup as a household/startup house” and post-pandemic office-home boom? Why do we keep relearning the dangers for women in these spaces every few years, but continually sacrifice our best and brightest without any changes to its fundamental workplace dynamics?

To understand the startup house, we must first understand the home.

And the home does not exist without women’s work.

The mental load is a term for the invisible labor involved in managing a household and family, which typically falls on women's shoulders. The mental load should not be mistaken for the physical tasks themselves, but rather, the overseeing, organizing, and remembering of those tasks. As the American Sociological Review explains, women are expected to “anticipate needs, identify options for filling them, making decisions, and monitoring progress."

What is crucial about the mental load is that division of labor is not the solution. Women do not lighten the mental toll by telling men what to do; that is fundamentally beside the point, if not validation of the very problem itself. In a household, even if a woman is running physically fewer errands, she is likely still in charge of checking the fridge, telling her partner what food to pick up, planning the meals, and remembering what snacks her kids like or don’t like. As the French artist, Emma Clit, shows in her renowned comic, You Should’ve Asked,

“When a man expects his partner to ask him to do things, he’s viewing her as the manager of household chores. So it’s up to her to know what needs to be done and when. The problem with that, is that planning and organizing things is already a full-time job. At work, once I started managing projects, I quickly stopped participating in them. I didn’t have the time. So when we ask women to take on this act of organization, and at the same time to execute a large portion, in the end, it represents 75% of the work.”

Unsurprisingly, the mental load easily carries into the workplace, where “invisible labor” transforms into “office housework.” In the United States, workplaces are still dominated by men; women represent 45% of the S&P 500 workforce but only 4% of the CEOs. In a study of nearly 22,000 publicly traded organizations worldwide, 60% still have no female board members. In 2022, women still only earn 82 cents for every $1 men earn.

More than a century after women entered the workforce, they are still desperately fighting for a seat at the table and better conditions wherever they can. When they do get a chance, they do it very well. According to the 2021 report on “Women in the Workplace” from McKinsey & Company, which surveyed more than 400 companies and more than 65,000 employees in professional jobs from the entry-level to the C-suite:

At all levels of management, women showed up as better leaders, more consistently supporting employees and championing DEI. Compared to men in similar roles, women managers invest more in helping employees navigate work-life challenges, ensuring workloads are manageable, and providing emotional support. Women managers are also more likely to act as allies to women of color by speaking out against bias and advocating for opportunities for them. Finally, women leaders are also more likely than men to spend time on DEI work outside of their formal job responsibilities, such as leading or participating in employee resource groups (ERGs) and serving on DEI committees. Among women at the manager level and above, Black women, LGBTQ+ women, and women with disabilities are up to twice as likely as women overall to spend a substantial amount of time promoting DEI.

Clearly, women are a good bet in workplaces. But the reason why women are able to outperform men in this way is far more alarming than comforting: it’s because they are disproportionately volunteering to do it. Women tend to overextend themselves in both the house and the workplace; they are natural managers because they are socially conditioned repeatedly throughout life to be one. As the report points out:

Compared to men in similar roles, women leaders are more likely to be exhausted and chronically stressed at work. Alarmingly, more than half of women leaders who manage teams say that over the last few months, they have felt burned out at work ‘often’ or ‘almost always,’ and almost 40% of them have considered downshifting their careers (for example, by moving to part-time work) or leaving the workforce altogether. What’s more is that this work is going unrecognized. Only about a quarter of employees say that the extra work they’re doing is formally recognized (for example, in performance reviews) either ‘a great deal’ or ‘a substantial amount.’

So where do women go? They go to tech jobs, which are known for flexible schedules, more lucrative pay, and progressive values; companies like Microsoft offer up to $1,500 in “wellness stipends” to help their employees stay fit and well while Google provides 6-months of paid maternity leave. However, tech itself is still heavily male-dominated. So for women interested in more recognition and/or weight in a company, a change of pace, or the chance to build something new within tech, they turn to the heart of Silicon Valley: startups.

Co-founder Vidit Jain of ShopClues once described startups as, “the place to be. If I had joined any of the big companies I would not have gotten so many opportunities. There is a huge difference between the opportunities I am getting here compared to the ones I was getting in my last company.” And it’s true: many of the traits that draw talented and ambitious individuals to startups are unique to its workplace modus operandi, especially during the last few years’ general startup house boom and the 2022 Big Tech layoffs.

Startup tells us this: you give the company your all and it will reward you. As long as your ideas are good and you are pulling your weight, then you will reap the reward. Everyone is working towards the same mission, sitting in on the same meetings, and has the same skin in the game. Startups typically leave 10-15% of equity for employees, with some early members owning as much as 1% of the entire company. It is common for roles and job responsibilities to be unclear and for everyone to be a "generalist," taking on as many tasks as they can to help the company grow and scale quickly. The values are unpretentious: celebrating scrappiness, collective ownership, and new ideas over bureaucracy, individualism, and tradition. These are the same ideals labor activists and feminists have been advocating for decades…so where do startup houses go so wrong?

The problem is that startups don’t start by hiring for roles like janitors, office managers, human resources, or other non-technical assistants—they can’t afford to. You may be building a company in your house, but that does not mean that running the company translates to running the home; teammates need to be fed, trash needs to be taken out, dishes need to be done, and spaces need to be cleaned. Thus, many of the household or non-building responsibilities at these startup houses, like ordering snacks, setting up spaces in the office, or anything involving the word “plan,” tends to fall on the women of the team, regardless of what their salaried role is. These quiet tasks women accept—and the extra organization, memorization, and anticipation it requires—reinforce gender imbalances in the workplace, creating an unsafe environment that is prone to sexual assault and violence.

If anything, startup environments are an example of the workplace, regressed: no one expects protections for women because no one expects work-life protections for anyone. It counts on you being the type of person to take on the invisible work. Even though females are still the minority at startups, they suffer the majority of this mentality’s consequences, feeling pressure to step up and over-extend to the point where they brush off experiences of sexual harassment at work.

The sad truth is that women are socially conditioned from a young age to maximize helpfulness and the comfort of those around them; we are the first to apologize, the first to start planning, and the ones most likely to believe that by taking on more responsibilities, especially those outside our current role, we prove our competency and commitment to a company…which is a fundamental fallacy, because the only thing we really prove is that we are willing to do more work (and keep those responsibilities) for far less (salary-wise, recognition-wise).

Why did Jessica return to Launch House after her sexual assault?

Startup asks us: well, why not?

We give and give and give only to realize that this fallacy never applies to men because men have never been conditioned by society-at-large to feel undeserving or “lucky” to be where they are; to men, it is by sheer hard work alone that they are where they are. Perhaps that is true—it is by hard work alone, because they have never feared what women fear in the workplace: that the worst day of their life may not be the day they are very likely passed up for a promotion, but that the one where they join the 40% of women in tech who are sexually assaulted by someone from work.

So sure, you can call Silicon Valley the home of innovation. But is it a home we want to return to as the second Golden Age of startup arrives? And is it one we can even pretend to welcome ambitious, talented women into?

If the solution is to simply create an environment where women are not disproportionately compelled to volunteer their work, life, and even body in order to receive recognition, appreciation, or opportunities, then where does that leave the foundation of startups? Can it even be done?

Honestly, I don’t know.

But it’s not a woman’s job to tell you the answer, anyways.